This November sees the arrival of Lester, a rotoscoping-based 2D animation editor specially aimed at indie retro game developers and pixel artists. Developed by Ruben Tous from the Universitat Politècnica de Catalunya (Spain), Lester is distributed as a free desktop application. The editor streamlines the repetitive aspects of rotoscoping, particularly the propagation of masks across frames. In an era dominated by generative AI, it’s refreshing to see tools focused on genuinely supporting artists in their craft.

In industries such as cinema or video games, rotoscoping has been traditionally employed to leverage the information from live-action footage for the creation of 2D animations. This technique contributed to the emergence of a unique visual aesthetic in certain iconic video games from the 80s and 90s, such as Jordan Mechner’s "Prince of Persia" (1989), Éric Chahi’s "Another World" (1991) or "Flashback" (1992). That legacy persists in modern indie titles such as Johan Vinet's "Lunark" (2023), that draw from the same aesthetic, and Lester positions itself as a practical bridge between the charm of those classics and the realities of independent production today. By automating repetitive frame-to-frame adjustments while preserving the precise shapes and choices made by the artist, the tool aims to make rotoscoping feasible for small teams and solo developers who previously might have avoided the technique because of its labor demands.

Unless most part of software today, Lester is a local desktop application, does not require Internet connection and its free. The application is available for both macOS and Windows; the Windows build includes an optional GPU-accelerated version for faster processing, while a CPU-only variant is available for machines without dedicated graphics hardware. It's important to note that Lester is currently at version 0.1.11-alpha. While the tool is fully usable and capable of producing professional results, it remains in active development. Users should expect occasional bugs and evolving features as the software matures. Although Lester is suitable for a range of animators, it has been created with a particular audience in mind: indie retro game developers and pixel artists. These creators often seek the lifelike motion rotoscoping can provide but need output that can be stylized into low-resolution sprites, simplified line work, or palette-limited art. Lester lets them extract clean silhouettes and simplified shapes from video, refine those shapes to match a chosen aesthetic, and produce frame sequences that are easy to convert into pixel art or schematic animation. For a solo developer building a small game with a cinematic feel, or a pixel artist wanting realistic but stylized walk cycles and gestures, the tool offers a way to achieve those ambitions without a full animation staff.

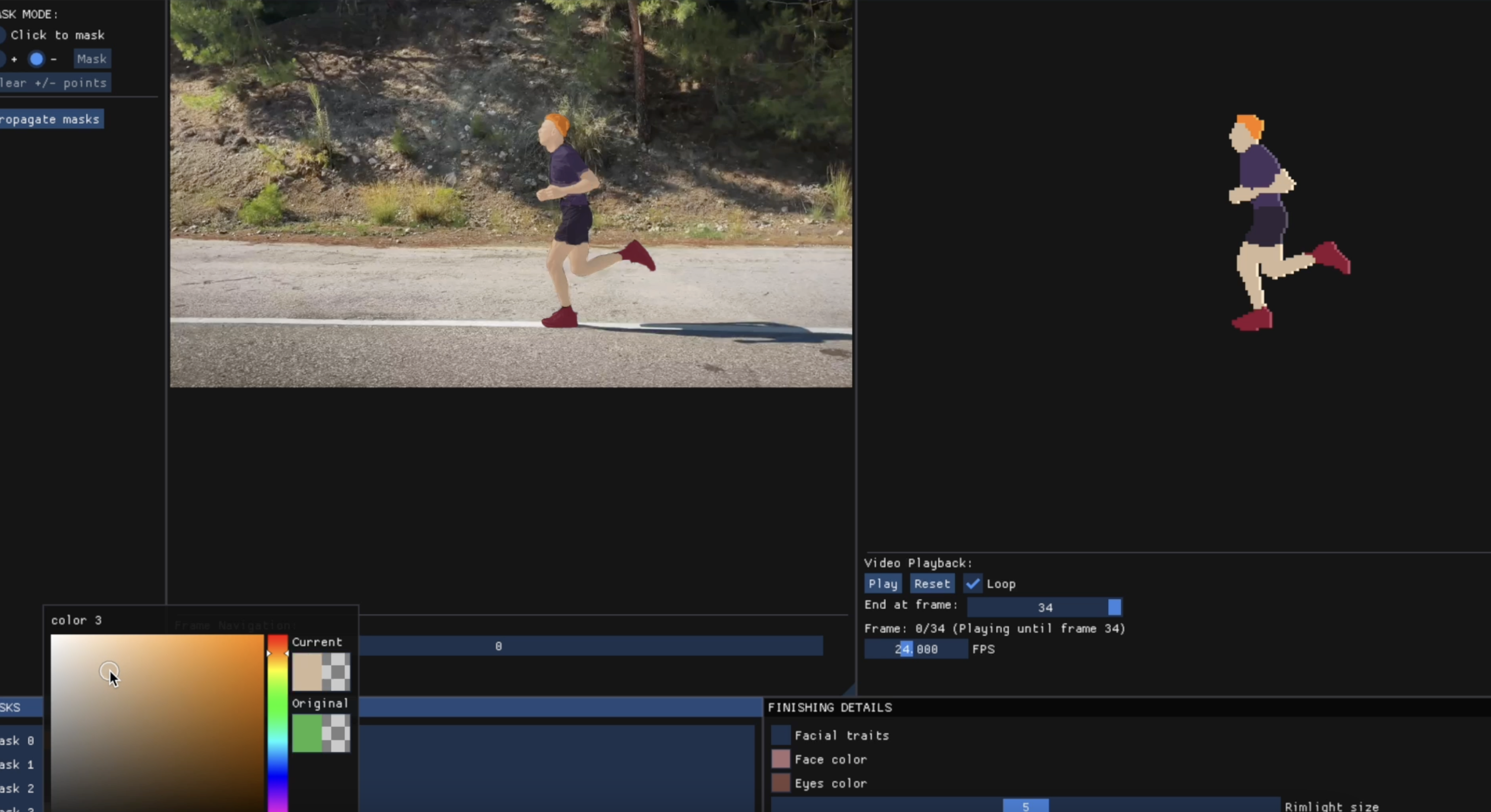

Internally, Lester is based on the method described in the research article “Lester: Rotoscope Animation through Video Object Segmentation and Tracking”, published in July of last year. Using a set of coordinates provided by the user—clicks on the first frame of the reference video—the system identifies a region or mask to be selected (for example, a jacket or a hat). These coordinates can be positive (if they fall inside the region) or negative (if they fall outside it), and with that information the method generates a colored mask. The initial mask usually has contours that are too irregular, so the system applies the classic Douglas–Peucker contour-simplification algorithm, which gives the shapes a more geometric finish. The editor allows users to customize the color of the masks—including some classic palettes such as EGA—and apply additional effects, such as different pixelation levels or a rim light. Lester’s most powerful feature, unavailable in any existing commercial application, is the automatic propagation of masks to the rest of the video frames. With a single click, all user-defined masks are transferred across the entire sequence, adjusting their shape and position to the movements and changes that occur in the video. Even if a mask disappears from a particular frame, it can be recovered if it reappears later on. The results are very strong, although this operation is computationally expensive and may take several minutes when there are many frames to process. Optimal performance is achieved on a machine equipped with an NVIDIA GPU or, to a lesser extent, with an Apple processor; however, with some patience it is also usable on a Windows computer without a dedicated GPU. One way to reduce processing time is to lower the number of frames in the video, something the tool itself allows. To compensate for that reduction, the editor offers the option to add frames through interpolation at the end of the process. As an additional feature, Lester can also automatically add geometric facial features, similar to those seen in the game Another World.

The context of Lester’s release matters as much as the software itself. In a software landscape dominated by subscription services and cloud-based AI offerings, a small, locally run, free tool crafted for independent creators feels like a deliberate counterpoint. The single-developer origin of the project gives it a particular ethos: it was built to solve real problems faced by individual artists and small teams, rather than as a showcase for monetization strategies. That sensibility will likely resonate with hobbyists, experimental filmmakers, and small studios that value transparency, portability and a workflow they can fully understand and control.

Lester will not replace the tradition of hand-drawn animation, nor is it intended to. What it offers is a pragmatic pathway to bring live-action reference into stylized, frame-accurate 2D animation without the historically high cost in time and manpower. For indie developers chasing that retro cinematic look, and for pixel artists who want the richness of natural motion condensed into a limited palette or a reduced resolution, the tool represents an accessible way to pursue ambitious visual goals. If more creators begin to adopt rotoscoping because the barrier to entry has been lowered, we may see a fresh wave of retro-inspired projects that blend classic animation sensibilities with contemporary independence.

For now, Lester’s debut this November is best seen as an invitation: an invitation to experiment, to reclaim a powerful animation technique, and to do so on terms that respect the artist’s ownership and vision. Whether you are a solo indie developer polishing a pixelated protagonist’s run cycle, a freelance animator exploring stylized motion, or a small studio seeking predictable production tools, Lester is worth a look — a small, local-first tool that makes a traditionally costly technique far more accessible.